I just read a good book that I’d hesitate recommending to my friends.

Most of my friends are avid readers. Some of them mainly read books connected to their fields of study, which in my friends’ collective case is largely literature and history; many of them sample multiple genres, including crime fiction; most of them value the craft of writing highly. So why wouldn’t I recommend a well-written, interesting detective novel set in South Africa?

The 2012 Soho Press reprint of The Steam Pig, complete with blandly generic cover

The book in question is The Steam Pig, a novel written by an Anglophone South African named James McClure, published in 1971. It’s the first in an award-winning series featuring Lieutenant Trompie Kramer, an Afrikaner detective, and his something-close-to-partner, the Zulu policeman Mickey Zondi. The plot involves crooked English-speaking politicians, loutish Afrikaners, transgressive sex rings, Coloureds passing for white, ‘Bantu’ gangs, and Indian stoolies as they clot around a mysterious murder. It takes place in the provincial city of ‘Trekkersburg,’ based on Pietermaritzburg, where McClure spent his youth.

Just my cup of bush tea (oh, wait: The Steam Pig is not a charming No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency yarn, although it may be a rough predecessor). My father transmitted his enjoyment of Ed McBain’s ‘87th Precinct’ procedurals and John D. McDonald’s ‘Travis McGee’ detective series to me when I was in grade school; my fascination with ‘Africa’ was in full flourish by the time I was ten (I still have two of the first books I bought with my own money, ‘Teach Yourself Afrikaans’ and ‘Teach Yourself Swahili’). So how fun was it to ‘discover’ The Steam Pig a couple of days ago (thanks to Book Bub’s cheap or free e-book offerings)!

Earlier covers of The Steam Pig, suggesting racial and sexual menace

Apart from this conglomeration of personal interests, I admire McClure’s arresting prose. He’s adept at jolting but apt comparisons, such as Kramer’s thoughts while looking at a victim laid out in the morgue, just after having speculated on the duration and violence of her death: ”The association of violent action with the violently inactive Miss Le Roux had the subtle obscenity of a warm lavatory seat.” He drops unexpected aphorisms: “Hell hath no fury like a jilted hypochondriac.” Perhaps most admirably, he can condense layered socio-economic realities into a relatively brief description, like this about a well-maintained road bisecting a squalid township: “It took the vulnerable white motorist through as quickly as possible, reducing the shacks and shanties to a colourful blur, and provided an excellent surface for the deployment of military vehicles in the event of a civil disturbance.”

A Spanish language edition’s cover obscures any reference to race and sex, settling instead for what may be a depiction of South African mining (not an overt issue in the novel)

And yet . . . as I read, I grew increasingly uncomfortable. Wogs, kaffirs, Jewboys, curry-guts, coolie-marys, trying-for-white: the seemingly casual slurs were, to say the least, offputting. Because the book was published in the early 1970s, when South Africa was fully in the grip of Apartheid, I didn’t know what to make of its vocabulary or its matter-of-fact references to police brutality, prison beatings, pass law abuses, segregated living areas, and the like. Is it neutral reportage in fictional guise, condemnatory exposure, or plain old complicity?

I know little about the author, James McClure, except that he was a fairly successful working journalist who emigrated to England, where he kept churning out Kramer and Zondi novels while pursuing a career as reporter and newspaper manager (he died in Oxford, in 2005). It’s quite possible to read The Steam Pig as a subtly satiric South African police procedural, particularly because it has at its center the respect, mutual dependence, even something approaching friendship between the Boer and the Zulu. On the other hand, the sheer onslaught of racialisms and Apartheid-motivated deprivations presented as business-as-usual makes a contemporary reader blanch.

James McClure in London

It’s nice to think that McClure was trying to expose the racially-vectored moral rot of Apartheid . . . as carefully as possible, given the Draconian censorship regime. Even if that were his intent, was it evident at the time he wrote and is it discernable now, when so much has changed in regards to acceptable vocabulary and prevailing socio-political attitudes? (Apparently, the Kramer and Zondi novels are not well-received in South Africa any more). Or does it even matter, as The Steam Pig remains a compulsively readable (and often republished) document of racial attitudes and their consequences in a particular time and place? Yet a basically repellent one? Has a good book gone bad due to shifts in readerly expectations, ’tolerances,’ and historical memory?

People have asked similar questions about ‘British Colonial’ literature ranging from Rudyard Kipling’s Kim to Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden. Such canonical works, which contain no-longer-politically-correct words and attitudes, have been subject to de-canonization campaigns, as have Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle series (out of print for decades until filmic and bowdlerization rescue), George Remi/Herge’s Tintin series, and Jean de Brunhoff’s Babar series. Not to mention, on this side of the Atlantic, Samuel Clemens/Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or, more recently (and back on the other side of the Atlantic), Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, with its Central African Oompah-Loompah slaves.

Illustration from Tintin in the Congo (1930-1931)

These books, however, are or were initially classified as ‘children’s books’ — in other words, books that would provide innocent amusement, perhaps edification, but would not expose young readers to troubling or morally corrosive ideas. (Recently, ‘children’s books’ have opened to controversial subjects . . . if they are presented in sensitive and politically digestible ways.)

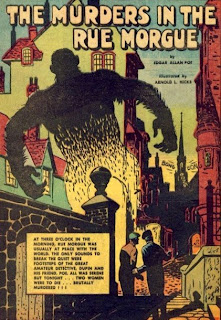

Further, children’s books (understandably) have not been held to the same standards as ‘serious’ adult fiction. Neither are detective novels or police procedurals — which may be why the overt racism in, say, Edgar Allen Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue” or Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventures of the Three Gables” is pretty much overlooked, not to mention that the authors in question are fairly firmly ensconced in the Western canon (and thus in the academic publishing-and-reputation industry). In addition, there may be an underlying assumption that crime fiction afficionados are incapable of applying historical context, irony, and trans-cultural knowledge to what they read. Rather like children.

Arnold Lorne Hicks, artist, “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Classic Comics, 1943, highlighting an un-orangutanly bestial urban menace

Is it easier, therefore, to turn a good book into a bad book if its genre is marginal, its target audience is deemed to be unsophisticated, and the author is not bullet-proof? Is it easier if the currently offending material is racist/imperialist/white man’s burdenish rather than, say, sexist? Isn’t much of the Western Canon (and for that matter, the great works of ‘World Literature’) patriarchically grounded if not outrightly misogynist?

Jane Eyre, for instance, has spawned a cottage industry of soft-erotic (often self-published) contra-feminist continuations, such as Janet Mullaney’s 2014 novelette

All this makes my hair hurt. I have no desire to reengage the canon wars, or the what-is-great-literature-wars, or the what-should-or-shouldn’t-be-taught (or republished) wars. But reading The Steam Pig has brought these always contentious issues slinking back into everyday life. Should I write a blog about this rather astonishing book? If I were still university professing, would I include it on a syllabus (and for which class)?

I suppose that by writing here about McClure’s South African series, and doing so while raising questions about its palatability, is a roundabout way of recommending the book. I guess. Maybe. Thank goodness (or badness) it’s now cocktail hour at the local shebeen.

No comments:

Post a Comment